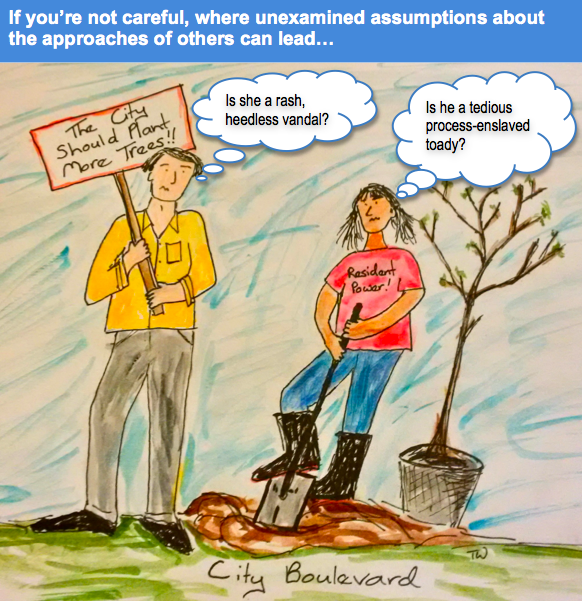

Ever experienced a community process where you shared a common objective with others but your approaches seemed worlds apart and maybe even resulted in strife and conflict?

Ever experienced a community process where you shared a common objective with others but your approaches seemed worlds apart and maybe even resulted in strife and conflict?

Such a situation often seems all too common and can be demoralizing. Even more so, conflict over styles of approach has real implications in terms of our ability to make change happen.

So, if how we come together matters as much as what we’re trying to accomplish, this post is about trying to daylight some of the assumptions each of holds on how best to change the world. Having a sense of the “activist worldview” that you bring to the table goes a long way in understanding that of others and reducing conflict before it starts.

What the Heck do I Mean by “Activist Worldview”?

For the purposes of this post, I’m using the term “activist” to mean anyone who is willfully trying to improve their society and/or planet. I would have included my 97-year-old Gran in this category even though she–like many–would have likely scoffed at this word and said it only applied to ruffian hoodie-clad young folks.

“There are two kinds of people in this world: Those who believe there are two kinds of people in this world and those who are smart enough to know better.” — Tom Robbins, Still Life with Woodpecker

And as for “worldview,” I’m going to use that term here as shorthand for some sweeping generalizations about how people see power and the best ways to make change. For ease of discussion, I’m going to violate Mr. Robbins’ quote about “two kinds of people” and clump them into two. However, I can’t underscore enough that in actuality we’re dealing with a spectrum of approaches and not really either/or.

Perceiving Power and Change

About a decade ago I encountered an idea that I thought explained a lot about why I was seeing strife happen in groups around me.* Coming out of then emerging practices like participatory budgeting and David Engwicht‘s work on street reclaiming, the idea named those direct citizen actions (which I’m calling here “We ARE They, Let’s Just Do This” approaches) as something separate from “traditional advocacy” approaches. Giving them a name provided a way to talk about them. Here’s the gist of how they differ:

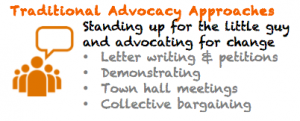

Traditional Advocacy is typically based on a perception that there are two groups and a divide between them: those in power (who make the laws or decisions) and those who are affected by those decisions. The role of activists in this model tends to be standing up for the “powerless,” keeping the powerful in check, and trying to influence the decision-makers.

Traditional Advocacy is typically based on a perception that there are two groups and a divide between them: those in power (who make the laws or decisions) and those who are affected by those decisions. The role of activists in this model tends to be standing up for the “powerless,” keeping the powerful in check, and trying to influence the decision-makers.

- Some of the approaches associated with this worldview include well-used tools to influence City Hall (letter writing, petitions, demonstrations, town hall meetings) or employers (collective bargaining, job action, etc.)

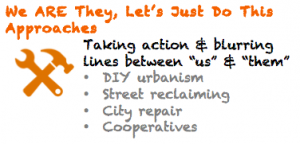

We ARE They, Let’s Just Do This approaches tend to blur the lines between the two camps of traditional advocacy and in fact may ignore them or step away from them altogether. The role of activists in this model tends to be saying “we ARE the city, established process isn’t working, let’s just take action.” It may also involve creating structures where the previously “powerless” are in charge.

We ARE They, Let’s Just Do This approaches tend to blur the lines between the two camps of traditional advocacy and in fact may ignore them or step away from them altogether. The role of activists in this model tends to be saying “we ARE the city, established process isn’t working, let’s just take action.” It may also involve creating structures where the previously “powerless” are in charge.

- Many of the ideas associated with DIY urbanism and street reclaiming fit here, where citizens take it upon themselves to address issues or make change in the city without necessarily following typical process or asking permission. I also believe that structures where citizens or employees are given true decision-making and implementation powers–and not just “consulted” as stakeholders–are at this end of the spectrum (cooperatives, city repair, etc.)

The important thing to note about my descriptions above is that I’m trying to group collections of approaches not people. I recently read Mike Lydon and Anthony Garcia’s book Tactical Urbanism and one thing I liked about it was their point that cities themselves can (and do!) engage in approaches that are closer to the “Let’s Just Do This” end of the spectrum. Again, it’s about how we perceive power and seek to implement change. It’s as possible for the New York Department of Transportation to implement “Let’s Just Do This” approaches as it is for grassroots groups to follow the path of “traditional advocacy.”

A temporary installation of traffic cones to change how road space was allocated in Hamilton, ON. (Photo by Philip Toms, from Tactical Urbanism)

It also key to note that solving different issues requires different sets of approaches and that all have value. As much as I would like to head out in the wee hours with a drill, concrete bit and about 5,000 traffic cones to create 15km of DIY bus lanes overnight in my hometown, I (grudgingly and professionally) know that ultimately the creation of lasting road network changes of that magnitude needs more coordination and process.

Similarly, keeping land, water and air safe from being ground up into a corporate bottom line requires a different set of tools than what I use when I’m lovingly digging up another swath of boulevard to plant more zucchini.

So Then, What’s the Big Deal?

I’m raising this point because while we may draw from different approaches along the spectrum, I believe that each of us naturally favors a certain set. Our activist worldview will have been shaped by age, culture, upbringing, perceptions of authority, habit, hard knocks experience and a whole lot of other things. But like being left-handed or right-handed, one set of approaches will just feel more comfortable.

Where different approach styles play havoc is in situations where we haven’t acknowledged that we have a tendency one way or the other and our approach tendencies and assumptions collide with those of others. I’ve seen this collision happen in a number of different situations:

- In the case of resident’s associations or cycling organizations, I’ve seen examples where established organizations that have developed more “traditional advocacy” relationships and processes with city hall are then confronted with new members interested in “Let’s Just Do This” tactics: technically unauthorized acts of civic beautification, critical mass rides, etc.

- Older existing members may feel their organization’s reputation or long term success is threatened by these “rash” approaches. Newer members may perceive lack of established member interest in their ideas as stonewalling or reluctance to actually make change happen.

- In the case of placemaking, I’ve seen citizen-led efforts to change the city in small immediate ways questioned by activists who would rather focus their efforts on larger social justice issues and demonstrations.

- The placemakers may feel like they are actually trying to reach the same objectives as the demonstrating activists but are being undermined and belittled by them. On the other hand, the cynicism that builds in traditional activists observing these other activities may alienate them from folks who would actually be really helpful community allies.

- In my work with transit systems, the friction between the two world views sometimes presents itself when I am trying to directly involve front-line staff in making change. In some cases union leadership or system managers may be suspicious of participatory processes that blur a perceived union-management divide and their roles within it.

- For some union leaders, there may be reluctance to having members participate in decision-making or provide input that isn’t necessarily sanctioned by the larger group. Managers who may have more of a “command-and-control” bent may be leery of giving up power to a shared process. On the flip side, the reasons for this reluctance may be misinterpreted by the people trying to make transit systems more participatory or by front-line staff who don’t understand why they just can’t have their say in decisions so integral to their job satisfaction.

From Colliding to Complementing

There are a few things you can do to keep your larger objectives from being lost in worldview collisions:

1. Know yourself – You’re going to be far more effective in a group if you know where you fall on the above spectrum and are conscious of your own tendencies and perceptions.

- For Planners and elected officials working within cities, this also means having an awareness of where your organization is on the spectrum and looking at projects through both lenses: How might we increase the lightness and immediacy of a project while maintaining an appropriate level of control and transparency?

If you’re chairing a meeting where a worldview collision is occurring, try this: “I see that based on the different experiences of people in the group we’ve got a pretty wide range of suggested approaches to choose from. Let’s look at each of the options and see how we could put them together to make a plan.”

2. Acknowledge differences – The key step to avoiding the toxic conflict that may arise from different worldviews is to name the different styles of approach when they occur and stress that it’s about the characteristics of approaches not the characters of people associated with them. Having different opinions on which approach to use does not mean that people are less committed or not aiming to achieve the same end goals.

3. Address the approaches as layers of options not either/or. People are going to feel far more heard and you’re going to arrive at a better solution if you lay all the suggested approaches on the table and speak to them as suites of options to draw from.

4. Look at ways to address the underlying tensions of reputation and obedience. While people perceive power structures differently, often when a community group gets into strife over different approaches it’s because deeper concerns over reputation or playing by the rules are being triggered.

-

Sometimes you can address tension by finding a middle ground between two approaches. For instance, organizers of a “Kidical Mass” bike parade that was part of our neighbourhood’s annual celebration last year invited the Victoria Police Department to act as escorts for the ride. It was win-win-win:

- Kids and families still got to feel the power of taking over the whole street on their bikes

- Some of the organizers who might have felt leery about a full on “no permission needed we ARE traffic” critical mass ride didn’t have to sweat it

- The cops got to be cool kids and forge new relationships in the neighbourhood.

- Another technique is to enable smaller groups of members to tackle activities that the larger established group is reluctant to try. So for instance a larger resident association may focus on “official” petitions or lobbying while also enabling a small group of its members to “less officially” undertake complementing DIY action that brings attention to the issue.

- If you’re organizing a process, you can also bridge the two worldviews by creating a structure that allows for “official” and “unofficial” participants. This one has worked well in the case of enabling a diverse set of transit staff to be included in system decision-making. Process can be designed to have union leadership or managers “officially” provide their delegates or perspective and this complements the participation and feedback of other individual staff.

Bottom Line: We Need it All

There are many ways to make change in this world and there’s a role to play for each of the approaches. But most of all, in order to make change we need as many people as possible working together. That’s not going to happen if we’re too busy nitpicking each other over the how instead of focussing on the what.

*While thoughts on the implications of differing worldviews and how to address them are my own, I believe that I first encountered the description of the two types in a specific book. However, after two weeks of head scratching and tearing apart shelves full of books at home and at work, I still haven’t found the source. If you think you had the same reading list as me in the early 2000’s and know the source, please let me know.

Among my searches, there were some tremendous people who went out of their way to help me locate long-lost books that I thought might have been the source. Much thanks to Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute (one of the world’s leading transportation economists and a fellow I’m happy to have for a neighbour) and ace Sustainable Community Planner (and bass player) Pam Hartling and her fine colleagues at the District of Saanich’s Planning Department.

Who knew that when I set out to relocate an old book about community, by the very process I would come to appreciate just how lucky I am to have the community I do.

You rock! I wish I could find more of this type of ‘feel good and we can do here’ content for Atlanta – have thought of including facebook shares? on your site – I’m not tweeter.

Thanks so much for your comment, Karen. Do you mean a way to share these articles to facebook or a way of for others to post content to the site?

The buttons above enable sharing to Facebook and then a few months ago I created a Facebook page equivalent to Connecting Dots here: https://www.facebook.com/ConnectingDotsTransportation/ so that in theory folks could also comment and post. Do either of these fit with what you are thinking or are you looking for something even greater?

Saw your facebook post today and have “liked” the page, not sure how I could have missed it – great place to start!

Hadn’t done the “official” invite out to folks yet as I was still figuring out what the heck I was doing. But maybe I will now! Thanks so much for all your support, t